We hear a lot in recent weeks about the high cost of energy.

Recent studies, such as the latest report by the Centro Studi di Confindustria, show that Italian industrial production is in sharp decline. One of the main causes is the high cost of energy. Electricity alone had an increase of +450% in December 2021 over January 2021, i.e. in less than 12 months.

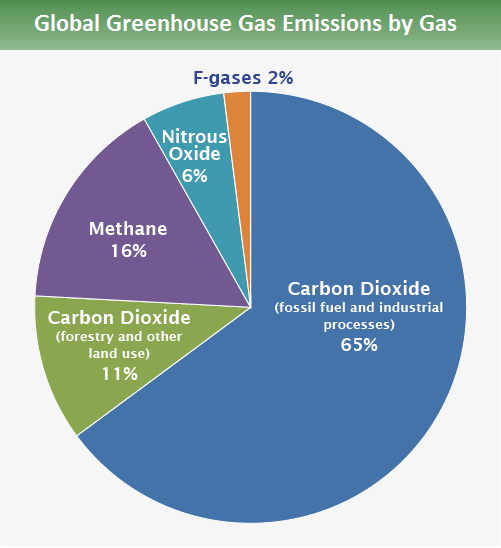

However, this figure must not be disconnected from a broader context: industrial activity must also be included among the variables that must be part of an overall plan to tackle climate change. All human activities that cause greenhouse gas emissions must be taken into account: some things, such as electricity and cars, get a lot of attention, but they are only the beginning. Cars, for example, are responsible for less than half of the emissions from transport, which itself accounts for ‘only’ 14% of global emissions. And there’s another figure that might come as a surprise: electricity production is responsible for ‘only’ a quarter of all emissions. And yet it has a huge impact on business competitiveness: why?

Because electricity is extremely cheap, and two-thirds of it is derived from fossil fuels, which are very cost-effective. They are widely available and we have developed extremely efficient techniques to extract them and turn them into electricity. Thinking of converting the entire electricity system to zero-emission sources would raise average prices even higher. We extract electricity from fossil fuels because it is cheap, yet the cost of energy has exploded, and if we wanted to go in the direction of zero-emission sources, the cost would rise further, bringing the production sector to its knees, not to mention the social consequences.

What to do? Let’s try to distinguish the three main stages of greenhouse gas emissions in industry:

1) we produce them when we use fossil fuels to generate the electricity that factories need to run;

2) we produce them when we use them to generate the heat needed for various production processes, such as smelting iron ore to make steel;

3) we produce it when we actually produce these materials, with the inevitable release of carbon dioxide in the process of making cement, for example.

In fact, it is precisely the industrial processes linked to the production of cement, steel and plastics that account for a further 21% of global emissions. Thinking about a climate plan without talking about these three industrial products (which I will discuss in a later section) could be a theoretical exercise.

We should therefore hypothesise a path to zero, or at least drastically limit, emissions in industrial activity and imagine a medium- to long-term way out of the difficulties currently caused by high energy prices. In a nutshell, I will try to list them:

- it is necessary to electrify all possible processes in industry. And this requires many technological innovations;

- If the previous point is to make sense, electricity must increasingly be obtained from a decarbonised-defoxilised source. This too will require many large-scale innovations.

- it is necessary to absorb residual emissions from industrial processes with technology that is already available (even if still at an experimental stage). Other innovations are still needed;

- more efficient materials must be used. Innovation.

In 2005, when the writer D.F. Wallace was asked to give a now-famous speech to the undergraduates of Kenyon College, it began like this:

“There are two young fish swimming side by side, and they run into an older fish who is swimming in the opposite direction and says, “Good morning, boys, how’s the water?” And the two young fishes keep swimming some more, and finally one of them turns to the other and says, “What the hell is the water?”

Wallace explained, “The basic point of the fish story is that the most obvious, ubiquitous and important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and hardest to talk about.”

This also applies to innovation: it is so pervasive that it can be difficult to grasp all the ways in which it touches our lives. We only notice it when it’s missing: starting with the amount we’ll see on our energy bills.