Is it possible to guarantee a healthy diet for a future population of 10 billion people while meeting the planet’s sustainability thresholds?

With a publication in the prestigious journal Nature Food, Marta Tuninetti, Luca Ridolfi and Francesco Laio of the Department of Environmental, Land and Infrastructure Engineering-DIATI of the Politecnico di Torino, propose an indicator, the Diet Gap, to measure the inadequacy of current food systems from the point of view of health and sustainability.

Eating habits are peculiar to the country in which we live and can be very different from those of other countries for reasons related to historical, religious, cultural, economic and social context: ‘we are what we eat’.

“According to the EAT-Lancet Commission, we should limit our weekly consumption of red meat to a maximum of 200 grams. On a global average, however, we exceed this limit by 2.5 times; in Europe it is exceeded by as much as four times, with major repercussions on health and the environment,” the authors of the article comment. “Looking at legume consumption, however, the Diet Gap shows that consumption is well below the ideal amount (about 100 grams a day), especially in more developed countries, where consumption of chickpeas, beans and lentils has been stagnant and below the threshold since the 1960s.

“Fruit and vegetable consumption, on the other hand, shows a more virtuous dynamic,” the authors continue, “since in many countries of the world the thresholds suggested by the commission (300 grams of vegetables per day and 200 grams of fruit) are respected.” However, the authors highlight the problem of so-called Food Deserts in some cities in the most developed countries, where finding fresh fruit and vegetables is often very difficult, especially for the poorest people.

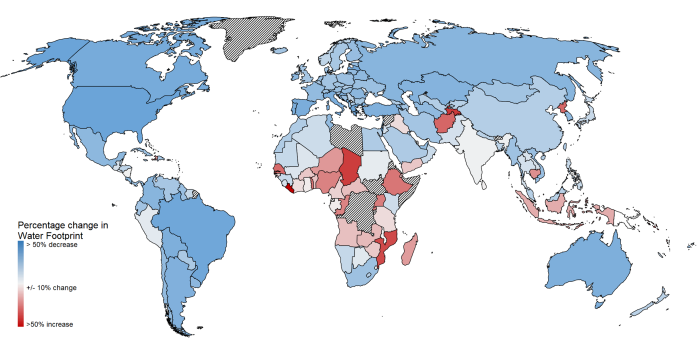

Overall, the study shows how a transition to a healthier food system implies a transition to a more sustainable food system. “If all countries adopted the EAT-Lancet diet, the water footprint would decrease by 12% on a global scale,” the authors comment. Food has very different water footprints: in Italy, 200 grams of lentils require about 900 litres of water, while 200 grams of beef requires more than twice that amount.

Concluding the study, the authors offer a broad overview of approaches to trigger the transition to a healthy and sustainable diet. These include consumer awareness and education, economic incentives to overcome barriers to healthy market access in urban food deserts, and taxation of carbonated soft drinks. Furthermore, improved refrigeration, food processing and sustainable packaging offer a key contribution to preserving the environment and improving public health. As suggested by the Commission, the Lancet diet is designed to be as versatile as possible and to include and promote different culinary experiences as an opportunity to learn new ways of preparing healthy and enjoyable diets (as demonstrated by the collection of recipes and food tips available online).